Alyce Santoro is an amazing West Texas artist. I had the pleasure of collaborating with her last year, when we premiered Unset in Marfa, Texas (one year ago today!). She is an inspiring creative force, and I am delighted she consented to an interview.

EM: How did you become interested in playing new music?

AS: I think my interest in playing new music must have begun with an early fascination for listening to the out-of-the-ordinary. I was fortunate to have been raised by parents who, while not musicians themselves, were very earnest listeners with eclectic tastes. Early on, I recall being exposed to Babatunde Olatunji, Ravi Shankar, and Oregon on vinyl records. In the New York metropolitan area we had access to incredible radio…in the mid-1980s I remember hearing Steve Reich, Philip Glass, Meredith Monk, and Laurie Anderson on WNYC’s New Sounds with John Schaefer. It was Laurie Anderson’s tape bow violin that inspired me to put an electric pick-up in my flute at age 15 or 16. At that time a group of misfit friends and I formed an experimental/improv/post-punk group…this was an extremely formative time for me, though we had no idea what we were doing, or where we could find guidance for our nascent interests in new and experimental music. Though I’d been playing the flute quite avidly as a young person, it seemed to me that the only options open to a flutist on the college level would be a strict study of classical music…which wasn’t really my interest. Morton Feldman and SUNY Buffalo, or music programs at places like Hampshire or Oberlin were just not on my radar. Instead I decided to study science as an undergraduate. After finishing a biology degree (with bioacoustics, sound, and music mixed in whenever possible), I went on to pursue a degree in scientific illustration. Though much of my current artwork has a visual bent – inspired in many ways by science – sound and music have always been part of the mix.

EM: You presented works of John Cage in Marfa a few years ago. What was the response?

AS: In 2012 my then-partner/now-husband composer/guitarist Julian Mock and I, with the help of a couple of friends, put together a program for John Cage’s 100th birthday. We presented it at the wonderful Marfa Book Company. For a town with a population of less than 2,000, we felt it was very well-received! Aside from the community performance of 4’33”, in which about 15 local musicians participated, the packed house seemed to enjoy the Improvisation for Amplified Cactus (regionally appropriate!), Pauline Oliveros’ Tuning Meditation, and several other works on the program. We definitely got the feeling that, while most attendees were at least somewhat familiar with Cage, some were being newly exposed. As part of the event, Marfa Public Radio featured a Cage special earlier in the day. All-in-all, we felt that Cage had been well-feted in rural West Texas!

EM: Your work ranges from theory to performance to instrument design to textile design, and I’m leaving out plenty. How would you describe the common thread that binds these varied directions?

AS: In general – no matter what medium I’m using – I’m looking for ways to highlight the interconnectedness of all things – disciplines, peoples, geographies, etc. I think of nearly everything I make as a collage…whether it’s a visual collage or a collage of sound, I am often weaving together seemingly-disparate elements as part of a kind of “delicate empiricist” (Goethe used this expression to describe science that allows for the qualitative in addition to the quantitative) approach to exploration into the Grand Unification Theory.

EM: Having left New York City for a relatively remote mountain town in Texas, you’ve maintained connections in a variety of ways. What have you found to be the most effective ways of staying connected to your artistic community? Do you feel more or less isolated than when you were in New York?

AS: I think of my website as a virtual studio, gallery, cabinet of curiosities, and archive. It’s important to me that anyone with a connection to the internet can freely access the information and ideas behind the work. In many cases, the pieces I make are ways of illustrating concepts…the ideas, to me, are often more important than the resulting artifacts. I’m grateful that these intangible elements can be shared and “owned” by anyone who comes in contact with them.

I never really expected or wanted to be a web designer or social media maven…but, for a creative practitioner who lives in a remote place and yet wishes to make work that is accessible, I find these skills essential. I use Facebook, Twitter, and am just getting started on Instagram. I also belong to several email lists for professional discourse related to the intersections of art, science, and ecology.

I also occasionally attend residency programs (Blue Mountain Center is one of my favorites) and conferences related to my fields of interest (for example, ISEA 2012 and New Music Gathering 2016).

Though I sometimes long for closer, more consistent proximity to fellow artists and receptive audiences, the environment in which I live has become so integral to my work that I hesitate to be away from it for any length of time. I think both urban and rural experiences can be isolating and aggregating in different ways…for me, alternating phases of each would be ideal.

EM: You’ve designed a new set of tools for cognition and practice of diatonic theory. Do you feel that a change is needed in the way music is taught? How do your materials fit into your ideal approach to teaching music?

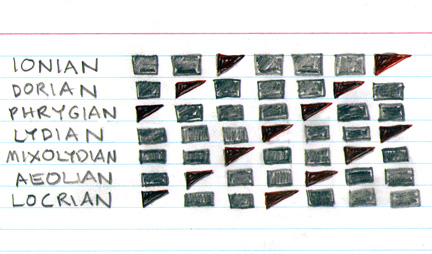

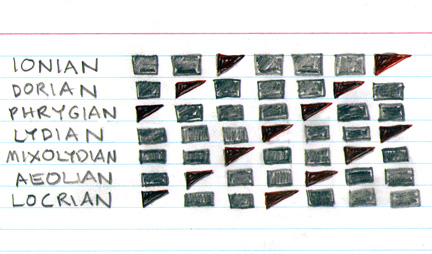

AS: As a flute player without advanced training in music theory, the Tonal Relativity project came out of my own desire to become more fluent in modality. I am always seeking to improve my skills as an improvisor. Over the years I’ve intermittently set out to study the modes, always coming away feeling like I wasn’t quite getting the big picture. Early last year I was determined to fully grasp the modes once and for all. I sat down with a 3-by-5 card and a pencil to make myself a kind of “cheat sheet”…I mapped the Modes of the Major Scale using shapes…squares for whole steps, and triangles for half steps. When I did this, a pattern was revealed that suddenly helped me to understand the modes as a holistic system.

Here is the original doodle on a 3-by-5 card that led to the development of the Tonal Relativity project:

I am no expert on the way music is taught, but I think the same is true in almost any discipline: gaining a full, functional understanding of a subject tends, in the long run, to produce far richer and more interesting results than, say, rote memorization. As a scientific illustrator, I am interested in figuring out ways to convey complex information efficiently. For me, the traditional methods of learning the modes weren’t clicking. I hope others – teachers, students, and independent practitioners alike – may find the Tonal Relativity project as useful as I am finding it!

EM: What would be your ideal artistic venture right now, and its ideal audience?

AS: I’m extremely interested in improvised music and interdisciplinary collaboration. With all that’s going on in the world, I feel there is much to be gleaned from the successes and failures of mid-20th century experimental communities like Black Mountain College, the Pulsa Group, and the Creative Music Studio. I have facilitated several “happenings” inspired by these collectives under the auspices of the Synergetic Omni-Solution, the Dialectic Revival, and the Obvious International. These events have, thus far, not been particularly music-oriented. My ideal now would be to facilitate or participate in kind of residency program in which listening, atmospheric phenomenology, and the exploration of musical/sonic ideas would be the central focus.

EM: What is on your music stand? Where will you next be playing?

AS: At the moment my stand is laden with theory books, staff paper, the Mode Charts, some compositions by my husband Julian Mock, and a stack of 3-by-5 cards with various musical ideas scrawled on them…these are frameworks for improvisations that Julian and I are working on collaboratively. We have been incorporating some of the modal ideas into partly composed, partly improvisational dialogs between the flute and guitar. I’ve got an exhibition coming up in spring 2017 at a gallery in Albuquerque in which the Tonal Relativity project will figure largely…we don’t have any concrete plans as yet, but these sound pieces will definitely be part of it!